March 09, 2018

Of the 41 states with broad-based personal income taxes, Illinois is one of eight with a flat tax rate. The Illinois Constitution requires everyone to pay a single statutory rate, regardless of taxable income. The other 33 states and the federal government have graduated income tax rates, with higher rates applied to higher income levels.

Should Illinois amend its constitution to allow graduated income tax rates? The issue has come up repeatedly in the past few years and has resurfaced in the gubernatorial election. Governor Bruce Rauner and his Republican challenger in the March primary election, State Representative Jeanne Ives, are opposed to a new tax rate structure, while most of the Democratic candidates are in favor of a change.

Proponents argue that graduated tax rates could provide needed revenue without placing an excessive burden on low income taxpayers. Illinois increased individual income tax rates from 3.75% to 4.95% in July 2017, but it still faces an operating deficit of $590 million in fiscal year 2018 and a $9.5 billion year-end backlog of unpaid bills. Opponents say overhauling the tax rate structure would aggravate the State’s financial problems by causing high earners to leave Illinois.

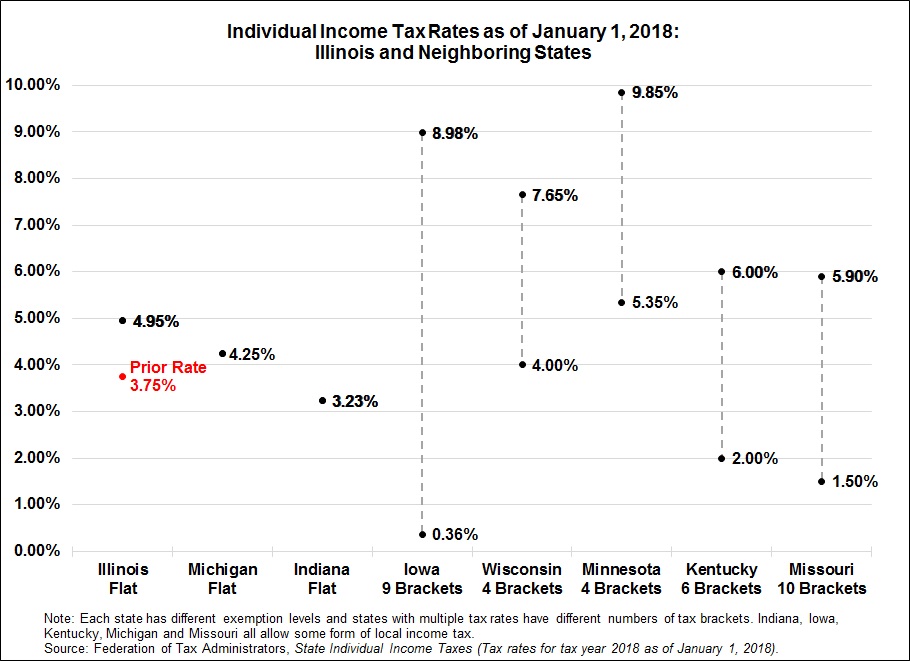

Comparing income tax systems across states is not easy. States with graduated rates have various brackets—income ranges that are taxed at the same rate. Each taxpayer pays the same rate on income in the first bracket; after that, income up to another threshold amount is taxed at a higher rate. The marginal tax rate is the rate applied to the last taxable dollar earned and is the top rate paid by each taxpayer. Within a state, there may be different brackets for single individuals and married couples.

Even states with flat tax rates have numerous exemptions, deductions and credits that alter the effective tax rate, the actual percentage of income paid in taxes. Some states, including Indiana, Iowa, Kentucky, Michigan and Missouri—but not Illinois—allow local governments to impose their own income taxes. Moreover, income taxes are only one of the many revenue sources that make up a state’s overall tax structure.

The following chart shows the top and bottom income tax rates in nearby states.

Since the Illinois General Assembly raised the individual income tax rate to 4.95%, Illinois now has a higher rate than either of the neighboring flat tax states: Indiana and Michigan. Insofar as Illinois competes with neighboring states on the basis of income tax rates, it is now at a disadvantage.

High earners in Illinois face a lower marginal tax rate than taxpayers in any of the nearby graduated income tax states. On the other hand, for low income taxpayers, who make up a much larger share of the population, Illinois’ flat tax rate is higher than the lowest brackets of all but one graduated income tax state.

The amount of revenue generated by a graduated tax depends on the tax rates and brackets. On the campaign trail in Illinois, most proponents of a graduated income tax have offered few details. An exception is Democratic gubernatorial candidate Bob Daiber, who has proposed on his web site a graduated income tax with five brackets and rates ranging from 1% to 6%, with only incomes of at least $1 million taxed above the current 4.95%. State Senator Daniel Biss, another Democratic candidate, has mentioned Wisconsin and Iowa as neighboring states with graduated income taxes. Wisconsin has four brackets and rates ranging from 4.0% to 7.65%, while Iowa has nine brackets with rates from 0.36% to 8.98%.

The Civic Federation, in its State of Illinois budget roadmap report for FY2019, proposed a comprehensive fiscal plan including restraining spending growth and broadening the tax base to include retirement income and sales taxes on certain services. A tax on federally taxable retirement income, which would not require a constitutional amendment, is estimated to bring in more than $2.5 billion annually at current rates. The report also recommended consideration of a modestly graduated income tax rate with a maximum spread between the highest and lowest rates of 3.0 percentage points. The proposed rate structure was intended to generate additional revenue, lower rates for low income taxpayers and protect taxpayers from excessive disparities.

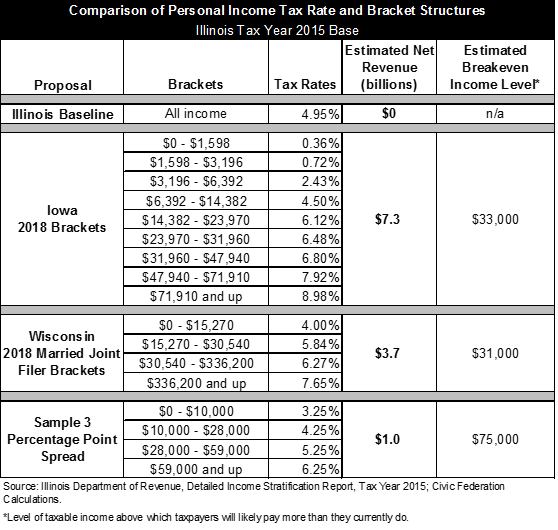

To estimate the revenue impact of various graduated rate structures, the Civic Federation requested detailed stratifications by adjusted gross income from the Illinois Department of Revenue (IDOR) for tax year 2015, the most recent year for which data is currently available.

First the Federation estimated the revenues that would be produced by applying the current Illinois tax rate of 4.95% to the 2015 tax base, then performed calculations to apply the brackets and rates currently used in Iowa and Wisconsin. In the case of Wisconsin, which has different brackets for single and married filers, the Federation used the latter for a more conservative revenue estimate. For comparison purposes, the model assumes the same exemption amounts and levels that occurred in Illinois in 2015.

Some caveats are in order. The first is that these are very rough estimates. To simplify the calculations it is assumed that all taxpayers within each income range provided by IDOR have equal incomes. While the data provided by the Department contains detailed income stratifications, it does not contain information on every deduction, adjustment, or credit on the 2015 Illinois 1040. To the extent that any proposal increases tax rates, some of the revenue to the State will be lost due to increased availability of non-refundable tax credits and various tax-avoidance strategies. Predicting the magnitude of these losses is extremely difficult without individual filing data.

Similarly, these estimates reflect collections by IDOR that are net of refunds, but before Earned Income Tax Credits are applied and before the State’s contribution to the Local Government Distributive Fund. As of January 2018, low income taxpayers with earned income receive 18% of the federal EITC amount as a refundable credit. In FY2018 local governments receive approximately 5.45% of net individual income tax collections.

Moreover, these estimates do not attempt to predict the economic impact in Illinois, which could have significant implications for the size of the tax base. Both the drag imposed by higher rates on high income taxpayers and the stimulus provided to lower income taxpayers would require complex economic modeling to accurately quantify. Finally, the estimates do not reflect the administrative expense associated with switching to a more complex tax regime.

For all of these reasons, these estimates should be regarded as representing the upper end of revenue that could be produced for the State by these proposals. With that warning, the following table presents the results of the analysis.

As the table shows, adopting Iowa’s or Wisconsin’s brackets would raise marginal tax rates on most Illinoisans and produce significant revenues for the State, at up to $7.3 billion and $3.7 billion, respectively.

The final column in the table shows the approximate breakeven level of taxable income for each plan, above which taxpayers would likely pay more in income taxes than currently in Illinois and below which they would likely pay less, depending on credits and other factors. These breakeven amounts are higher than the taxable income levels at which higher marginal tax rates first begin, because the total tax rate incorporates the lower marginal rates assessed on the first dollars of income. Even the highest income taxpayers receive a rate cut for the first dollars earned. It should also be noted that taxable income is usually less than adjusted gross income, which is the starting point for tax calculations. However, the Iowa and Wisconsin brackets would result in tax increases for many households in the middle class.

As mentioned above, the Civic Federation has cautioned the State that if it considers implementing a graduated income tax, the highest marginal rate should be no more than three percentage points greater than the lowest rate. A modest adjustment to Wisconsin’s rates would meet this restriction. As a final theoretical example, a bracket structure that began at 3.25% and charged each approximate successive quartile of taxpayers an additional percentage point would produce up to $970 million for the State. The breakeven point would be approximately $75,000.

Implementing any graduated income tax would take time and involve two parts: a constitutional amendment and legislation establishing new tax rates. An amendment would require approval by a three-fifths vote of each chamber of the General Assembly and could then be placed on the ballot in the next general election occurring at least six months after the legislature’s vote. In that election, the amendment would need the approval of either three-fifths of those voting on the question or a majority of those voting in the election.

Proposed amendments to allow graduated rates have been filed in the General Assembly in the past few years but have not passed. Similarly, a proposed amendment to increase State education funding by imposing a 3% surcharge on income over $1 million—known as a millionaire tax—was rejected by the House in 2016. In November 2014, voters overwhelmingly approved a non-binding referendum on whether such a millionaire tax amendment should be adopted.

Several proposed amendments for graduated rates are currently pending in the House and Senate, including SJRCA 1, SJRCA 16 and HJRCA 39. A pending House resolution states that that the flat rate should be retained.

The second part of a graduated income tax proposal involves changing State law to establish new graduated tax rates. House Bill 3522 proposes the same tax rates as in Wisconsin, ranging from 4.0% to 7.65%, but with different tax brackets. Another bill, House Bill 5818, directs the legislature’s Commission on Government Forecasting and Accountability to report on the impact of various graduated income tax rates.

A recent poll of registered voters by Southern Illinois University found that 72% favored amending the Illinois Constitution to allow for graduated income tax rates. Respondents were asked if they supported tax rates that would be lower for lower income taxpayers and higher for upper income taxpayers. However, the poll did not identify the income level at which taxpayers would be required to pay higher rates. In order to evaluate a specific graduated tax plan, voters would need to review the proposed tax rates and brackets.